Todd: Hello, Tor.com readers! We missed you, and it’s great to be back.

Howard: We didn’t actually go anywhere.

Todd: True enough. But it’s been a couple of years since we’ve collaborated on an article for the site. Those of you with long memories may remember some of our catchier titles, like “Five Classic Sword-and-Planet Sagas” and “Five Authors Who Taught Me How to Write Fantasy.” Today we’re going to continue the proud tradition of counting on our fingers by discussing the great works of short epic fantasy.

Howard: Maybe I’m a little rusty, but that topic makes no sense.

Todd: Stay with me. We’re talking about classic fantasy series that began as short stories, and evolved into something vaster and more ambitious.

Howard: Ah—now I get it. You’re right, the field has a lot of cool examples.

Todd: Let’s start at the top. For my money the master of the epic short story was Karl Edward Wagner.

Howard: You’re talking about the Kane books.

Todd: I am!

Howard: I’ve always thought of those as sword-and-sorcery?

Todd: The tales of Kane are as much gothic horror as they are sword-and-sorcery. Kane is a wanderer, a consummate warrior, and—although it’s not explicitly stated—it’s likely he is the biblical Cain.

Howard: The one who slew his brother.

Todd: That’s the guy.

Howard: Okay. We’re going to get to some heavyweights in a minute. Why do you consider Karl Edward Wagner the master?

Todd: You’ll find all the evidence you need in his 1973 novelette “The Dark Muse,” one of the finest sword-and-sorcery tales ever written. It’s the story of an ambitious poet who requests Kane’s help to summon the capricious muse of dream. In abandoned ruins at midnight the poet is finally drawn into a sorcerous dream, while all around him a crawling nightmare stealthily hunts Kane and his companions. It’s a terrifically moody tale of ancient secrets, betrayals, and twisted horror. And it really gets going when the poet finally awakens, and we get a glimpse of the dark secret he’s brought back from beyond the threshold of dream.

Howard: Okay, that sounds like a classic. And you’re absolutely right that Wagner was a major talent. He’s too often overlooked by modern readers.

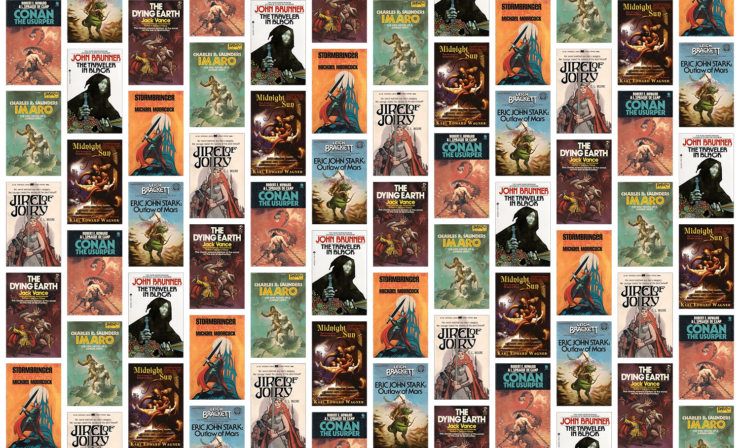

Todd: He wrote about twenty Kane stories. Like Moorcock before him, he eventually needed a larger canvas and turned to novels. He produced three: Bloodstone, Dark Crusade, and Darkness Weaves. Night Shade Press gathered them all in two omnibus collections, Gods in Darkness and Midnight Sun. They’re some of the best heroic fantasy on the market—if you’re in the mood for tales of a dark and cursed hero.

Howard: Glad you brought up Moorcock, because he’s one of those heavyweights I mentioned. Michael Moorcock’s Elric saga, part of his legendary Eternal Champion cycle, is one of the great works of modern fantasy. Believe it or not, Elric’s first appearance was 62 years ago.

Todd: That’s not possible.

Howard: Look it up. Elric of Melniboné is the last emperor of the decadent island nation of Melniboné. Burdened with both a conscience and a soul-sucking sword of awesome power, he carves a bloody path across the Young Kingdoms, on his way to his own inevitable doom. And it all began in the June 1961 issue of Science Fantasy, in the novella “The Dreaming City,” written when Moorcock was just twenty-one years old.

Buy the Book

The Citadel of Forgotten Myths

Todd: Damn. That’s extraordinary. Wasn’t the newest Elric novel, The Citadel of Forgotten Myths, just published in December?

Howard: Yup. A few days before Moorcock turned 83.

Todd: That’s serious literary longevity. Also, plain old regular longevity. I’m a little in awe here.

Howard: It all started as a sequence of connected short stories. In three short years after “The Dreaming City” dropped, Moorcock produced nearly a dozen more tales of Elric, all for Science Fantasy. The first novel, Stormbringer, was released in 1965. Many more followed, and you know the rest. Elric became hugely popular, and one of the defining heroes of modern epic fantasy. Short epic fantasy, as I guess you were talking about.

Todd: Told you it would make sense eventually.

Howard: I’m still not entirely sure the epic classification makes sense, but I’m just going to roll with it. Moorcock’s Elric is not just an innovative fantasy character brought to life with often stunningly lyrical prose, he’s also a completely new angle on sword-and-sorcery tropes and is almost a complete inversion of Conan—

Todd: Whoa, whoa. Let’s steer clear of a lengthy tangent on sword-and-sorcery.

Howard: Okay, sure. But staying with the theme of short story cycles, modern fantasy is thick with them, from Robert E. Howard’s Conan tales to C.L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry, John Brunner’s The Traveler in Black, and Charles Saunders’ Imaro. But I want to briefly come back to Stormbringer. Moorcock wanted to tell an ambitious, cohesive story, but he had only one outlet at the time.

Todd: John Carnell’s Science Fantasy magazine.

Howard: Exactly, and Carnell wasn’t buying novels. So Moorcock did what he knew how to do—he sold four separate novellas to Carnell. And in 1965, he stitched them together into a fix-up novel called Stormbringer, and that’s how the first Elric novel came to be.

Todd: Well, fix-up novels were how things were done in those days. Magazines were the primary outlet for almost all SF & fantasy. Asimov’s Foundation was a fix-up novel, built out of stories published in Astounding. So were Clifford D. Simak’s City, Walter M. Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, and Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles.

Howard: Sure, and we could talk about the historical fix-ups of Harold Lamb and Arthur D. Howden Smith that were actually hugely influential on fantasy. But I know you don’t want any of that icky historical stuff on your spaceships.

Todd: I’ll make an exception if we talk about Space Vikings. Space Vikings are cool.

Howard: If you want to talk cool—while he was in the US Merchant Marine during WW II, the legendary Jack Vance did something very cool. He produced one of the greatest fix-up novels of all time, The Dying Earth. Composed of six loosely-connected stories, it was immediately recognized as a major work of fantasy, and it vaulted Vance into the front rank of American fantasy.

Todd: That IS pretty cool.

Howard: I’m not even at the cool part yet.

Todd: Jesus, tell me already.

Howard: The problem with most fix-up novels was that for many readers, they were old news. They’d already read all the stories in major magazines. In The Dying Earth, Jack Vance gave readers precisely what they were expecting—a compelling episodic tale broken into easily-digestible chapters, sharing a setting and characters yet each complete and standalone. It was a comfortable format readers were used to. His innovation was simple: every story was brand new. Vance wrote a fix-up novel using stories that had never been published, and it became one of the most enduring works of fantasy of the 20th century. When Locus asked their readers to select the All Time Best Fantasy Novels in 1987, they ranked The Dying Earth #16.

Todd: Only Jack Vance. Let’s talk about a more modern series, one that began with the most successful example of a modern fix-up novel, and evolved into one of the top-selling epic fantasy series of the last few decades.

Howard: Give me a clue.

Todd: It’s also a western.

Howard: You’re making this up.

Todd: Nope. I’m talking about Stephen King’s The Dark Tower series, which began as a series of short stories featuring the gunslinger Roland, all published by Ed Ferman in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Howard: Here’s where I must shame-facedly admit I’ve never read much King, much less all seven volumes of The Dark Tower.

Todd: Hah! Weren’t you just lecturing me for not knowing the great historicals?

Howard: You and I view history very differently.

Todd: The first volume of The Dark Tower, The Gunslinger, is a fix-up novel composed of five short stories featuring Roland. It opens with the famous line, “The man in black fled across the desert, and the gunslinger followed,” and as you can probably guess, it’s a weird western. Emphasis on weird. King gives only the slightest hints of the vast backstory of The Dark Tower in these tight little stories, but they caused a minor sensation when they appeared, especially as it gradually became clear that the villainous Man in Black in these tales was Randall Flagg, one of King’s greatest villains and the primary antagonist of The Stand.

Howard: Let me guess. You have all these issues of F&SF in little plastic baggies.

Todd: They’re collector’s items!

Howard: Because you’re hoarding them all.

Todd: The Gunslinger is probably the most successful modern example of a short story sequence that gave birth to a popular epic fantasy series. Almost certainly it’s the one that folks today are most familiar with.

Howard: I feel like we need to make a demarcation between epic fantasy and short form. Because—and I’m sorry—that’s the maddest thing about your whole hypothesis. Epic fantasy is the polar opposite of these sorts of taut, short tales with crackerjack pacing. I’m not saying that epic fantasy isn’t good, just that it’s much more on the… glacial end of the pacing scale. It feels like a different beast.

Todd: You’re quibbling. Let’s spend our time talking about Leigh Brackett’s Stark stories instead.

Howard: Fair enough. I can’t believe such a talented writer is so little talked about today. She wrote fantastic science fiction adventure stories. Space opera? Sword-and-planet? Hardboiled science fantasy? Whatever you want to call what she did, she was aces, and writing about the kind of characters who would have been rubbing shoulders with the likes of Han Solo and Mal Reynolds long decades before those characters were ever conceived.

Todd: One of the last things she wrote was the first draft of The Empire Strikes Back—probably the thing she’s best remembered for today.

Howard: It makes me very sad that’s about the only thing people know about Brackett. I think she has two strikes against her, in terms of being better remembered. The first is that she wrote a lot of stories set in a solar system that everyone knows doesn’t exist.

Todd: The old pulp neighborhood—a habitable Venus, habitable Mars, even a Mercury with a twilight region where there’s a breathable atmosphere.

Howard: People can become invested in secondary worlds and distant planets with funny names where people live side by side with alien species, but it’s too old-fashioned to believe in a jungle-covered Venus these days. The second reason I think that she’s not better read today is that almost all of her work is standalone.

Todd: I never really thought of that. It’s probably true. One thing I find interesting about Brackett is that while her characters change, many of them share the same setting—a slowly dying Mars with dry seas and dead cities.

Howard: This all comes back to Brackett’s sole series character, Eric John Stark. She only wrote three short tales featuring Stark, and they’re all among her very best. I’m particularly fond of “Enchantress of Venus.” Stark is simply a great character, and later on she teamed him up with her husband Edmond Hamilton’s characters in another short adventure—but she eventually gave Stark an entire trilogy of novels, starting with The Hounds of Skaith. Apparently she had plans for at least one more, but she passed away from cancer. Which, incidentally, is the reason she only worked on the first draft of Empire.

Todd: Okay, serious question: Is the short epic fantasy series dead? It’s certainly nowhere near as prevalent as it used to be.

Howard: That’s true, whatever you want to call it.

Todd: I’m a huge fan of the format, but for years I was convinced that its day was done. Publishers simply had no appetite for it any more. But then you sold one to Baen. I’d love to know how you did it—this was once one of the most popular forms of fantasy, and I’ve been listening to writers lament its demise for twenty years. On behalf of an entire generation of frustrated fantasy writers, let me ask: How did you interest a modern publisher in something as old-school as a fix-up novel of short fantasy stories?

Howard: Hah! Well, I’m not sure it’s a standard fix-up, in that I planned from the start for the stories in each book to interlock and build off of each other toward a season climax. I think that’s part of what piqued Baen’s interest. The series is called The Chronicles of Hanuvar, and each book is like a season of a modern TV show in that each chapter DOES stand alone, but arcs build and conclude over several chapters, villains and sidekicks return, and each book closes with a season finale that wraps up all of the major arcs but leaves a few problems for the next one.

Todd: We talked about how important the setting and focus on worldbuilding was for Elric and the Dying Earth. Are you adhering to the same formula?

Howard: It’s limiting to think of it as a formula. But yes—setting is hugely important. This is a retelling of one of the great tales of antiquity, the fall of Carthage and its legendary general Hannibal. Volanus has fallen, and its people have been enslaved. The city’s treasuries were looted, its temples were defiled, and then, to sate their emperor’s thirst for vengeance, the empire’s mages cursed Volanus and sowed its fields with salt. They overlooked only one detail: Hanuvar, the greatest Volani general, escaped alive. Against the might of a vast empire, Hanuvar has only an aging sword arm, a lifetime of wisdom… and the greatest military mind in the world, set upon a single goal. No matter where they’ve been sent, from the festering capital to the furthest outpost of the Dervan Empire, Hanuvar will find his people. Every last one of them. And he will set them free.

Todd: I know you’ve said that you’re writing sword-and-sorcery or heroic fiction, but I want to say for the record that this sounds like epic fantasy to me. How long is the series?

Howard: Baen has signed me to a five book contract. The first novel, Lord of a Shattered Land was published on August 1st. The second book, The City of Marble and Blood, arrives October 3rd.

Todd: Okay, let me finish with this: what advice do you have for aspiring writers who have an old-school fix-up series they want to unleash on the world? Are the stars right at last? Or is there a secret to approaching publishers you can share?

Howard: Maybe it’s naive, but I don’t think the fix-up novel ever went out of style with readers. I think perhaps writers stopped modeling their work after Michael Moorcock and Robert E. Howard and Leigh Brackett, and instead suddenly everyone wanted to be J.R.R. Tolkien and George R.R. Martin. The market has featured long books starring grimdark protagonists for decades. But I don’t think heroes ever went out of style, and I think people will always respond to a rousing episodic series that gives them a satisfying ending every chapter—and frequently a new setting, a fresh set of villains, and a new challenge. Heroic fiction doesn’t mean you have to wait a generation to get a decent ending. It’s a simple concept, really.

Todd: Thank you Howard. Good luck with the books.

Howard: Thanks!

***

And now we’d like to hear from you—what are your favorite examples of epic stories that evolved or were woven together out of shorter tales, and which authors have done it best? Let us know in the comments!

Todd McAulty’s first novel The Robots of Gotham was published by John Joseph Adams Books in 2019. Under the name John O’Neill, he runs the World Fantasy Award-winning website Black Gate.

Howard Andrew Jones’s new sword-and-sorcery series debuted this August from Baen, starting with Lord of a Shattered Land and continues this October with The City of Marble and Blood. His Ring-Sworn trilogy, beginning with For the Killing of Kings, was critically acclaimed by Publisher’s Weekly. His debut historical fantasy novel, The Desert of Souls, was praised by influential publications like Library Journal, Kirkus, and Publisher’s Weekly. Its sequel, The Bones of the Old Ones, made the Barnes and Noble Best Fantasy Release of 2013 and received a starred review from Publisher’s Weekly. He is the author of four Pathfinder novels, numerous short stories, and edits the magazine Tales From the Magician’s Skull.

Delighted to have another one of these columns stuffed with classic swords and sorcery, though the lack of a mention for Fritz Leiber has me on edge. Surely Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser can’t have been forgotten?

Edit: Howard, FTFY:

“Heroic fiction doesn’t mean you have to wait a generation to maybe get an ending.”

I have to ask a question—are you sure you have the right name when you say Mal Evans? The only person I can find when I look up that name is a longtime friend/roadie for the Beatles. Did you mean Mal Reynolds?

“Short epic”? Isn’t that an oxymoron, like “cruel kindness” or “Army intelligence”?

Of course “Liane the Wayfarer”, from The Dying Earth, did have a magazine appearance — in the December 1950 issue of Worlds Beyond (edited by Damon Knight) under the title “The Loom of Darkness.” Not so coincidentally, the publisher of the magazine and the publisher of the book were one and the same: Hillman Periodicals. And almost certainly the book appeared before the magazine anyway.

Many of those early pieces — certainly the Brackett stories — were advertised as “Science Fiction” — “Sword and Planet”, if you will — but were really Fantasy, with a thin veneer of SF added to make them acceptable to the Science Fiction magazines of the time. And the Brackett stories — with or without Stark — are purely wonderful.(The Ace Double versions of the two Stark stories set on Mars, People of the Talisman (aka “Black Amazon of Mars”) and The Secret of Sinharat (aka “Queen of the Martian Catacombs”) are revised and expanded — the changes probably made by Edmond Hamilton.)

Two comments regarding Leigh Brackett:

First, I strongly agree that she is a great author who deserves to be better known. I particularly admire the way in which she took Eric John Stark, an outstanding character, and in her Skaith trilogy made him even better. Far too often when an author revives a beloved character it is a disappointing exercise in working to an old formula. Not Brackett! She took Stark interstellar.

Second, though as Todd said above, the “…old pulp neighborhood…” of a Solar System with multiple inhabitable planets is not something that is believable enough for a story background now it is interesting to note that current research is supporting the idea that Mars once had oceans. When Leigh Brackett wrote of the Sea Kings of Mars she may have been onto something!

I confess that my selection for a practitioner of short-epic fantasy may not be, by most, deemed a ‘master’, but I would nominate Lin Carter, whose works stretch out to epic length, but always in many smaller (bite-size?) chunks. And a number of them are fix-ups, so we can point to his predilection to turn a short story into a multi-volume saga. One of my reader-ly regrets is that he never made his Amalric the Man-God stories (2 only) into a fix-up, though he did write a series (The Chronicles of Kylix) that was set on the various planets of the star Kylix, one of which hosted Amalric and his comic adventures.

@1 – Schuyler, Fritz Leiber wasn’t forgotten! Maybe it’s a subtle thing, but I think of Leiber’s superb Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser tales as classic sword & sorcery, not epic fantasy,

I know it’s a strange distinction (I don’t think Howard agreed with it either). But Elric, Kane, the Dark Tower… they all started as linked short stories, then became fix-up novels, and then ACTUAL novels. That’s not true of Conan, and it’s not true of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser either. They stayed true to the S&S short story roots, and never graduated to the page-gobbling canvases of the novel series.

Doesn’t mean they’re not excellent, however. But they’re a different beast, in my eyes.

@2 – Maria, you’re almost certainly right. I think Howard meant Mal Reynolds, captain of the Firefly, and not the Beatles’ roadie.

But we’ll probably never know for sure.

@3 – Rick: Yes.

@@.-@ – Rich, I had no idea “Liane the Wayfarer” was published in WORLDS BEYOND. The title change meant that one flew under my radar.

You’re right that the Brackett stories “are purely wonderful.” Howard and I should devote a column just to her. She certainly deserves it.

@5 – Johnny, you’re right that the thinking on Mars has swung back to be (maybe) a little closer to Brackett’s vision.

But honestly, I’m not bothered in the least that these great old stories depict a Mars that’s not even close to accurate. As Rich Horton noted above (comment #4), these are fantasy tales dressed up as science fiction (and not very elaborately dressed up at that).

When I read Brackett’s tales she takes me back to a Mars that existed purely in her imagination, and I think that only adds to their allure.

@6 – Hey Eugene! Great to see you here. We’re usually swamping comments at the Black Gate website.

Howard is the Lin Carter fan; he’ll probably agree with you. I think Lin Carter may have been the finest fantasy anthologist of the 20th Century (Terry Carr and Gardner Dozois are his only competition), but his fiction never won me over.

On the other hand, I never read the Amalric the Man-God stories.

If I wanted to give Lin Carter another chance, where should I start?

@2 – Doh! Yes, I definitely meant Malcolm Reynolds.

I can’t ever talk for too long without somehow referencing The Beatles. At least we got through the entire article without me mentioning my other perennial subject, the original Star Trek… Whops, well, there that is too…

@1 – I seem to remember wanting to discuss Leiber and SOME co-writer of mine knocking that subject aside… But I think we’ve covered him in one of our other articles. As it happens, Leiber happens to be the first heroic fantasy/sword-and-sorcery I ever read, courtesy of *Swords Against Death*, and his work was one of the things that shifted my reading from space opera over to sword-and-sorcery and swashbuckling historicals.

More recently I’ve ended up editing a series of Lankhmar pastiches by Nathan Long that’s been appearing in *Tales From the Magician’s Skull*. So, yes, the Lankhmar tales hold a special place in my heart, or at least the first half of them.

@12 – Todd, Todd, Todd. How many years have I been telling you to read “Zingazar?” Since Black Gate was still in print, I think. It’s a short story that you can find in *New Worlds For Old* and while it’s variations on a “The Sword of Welleran” by Lord Dunsany it’s a minor heroic fiction masterwork.

Carter was never much of an innovator, but he has some stuff that can stand beside his peers, and his sheer love of what he’s doing always shines through. Probably his best heroic fantasy is the short novel *Lost World of Time.* If you have any affection for Burroughs style interplanetary adventure and frying pan to fire plotting, his Callisto books were a hoot. I can vouch for enjoying the first six slim volumes at least — someday I suppose I’ll read the final two.

His *Kellory the Warlock* is a fix-up novel of pretty enjoyable heroic fiction stories, and his six Thongor short stories are enjoyable, light Clonan style stuff. And some of his other Lord Dunsany style fiction is also enjoyable — that’s all been collected in a volume titled *Lin Carter’s Simrana Cycle.*

Why does the novel take precedence over the short story? Even a collection of stories from a single writer all in the same book seems to warrant greater attention than an anthology of writers, although I think S&S is one genre where the anthology gets more respect. And here’s a question about reader’s habits. Why read a collection or anthology straight through? Readers are not bound by publishers’ or editors’ decisions of how to organize a book. We can choose stories at our whim based on mood and desire.

I, for one, would like to hear a lengthy tangent on Sword & Sorcery!

One of the most pleasant surprises for me was discovering an old fantasy novel I picked up on a whim, Tanith Lee’s Cyrion, turned out to be a fix-up, it actually made me feel like we were getting more bang for our buck strangely enough.

@16 As far as collections, I think that’s a great question. I guess I have three approaches. If it’s an editor assembled anthology I often skip around depending upon my time versus story size, familiarity with the writer, or subject of the tale, but that may actually be a disservice. Jason Waltz has a new antho he’s working on (Neither Beg nor Yield) and pointed out he carefully orders the stories almost like he’s choosing album tracks to vary the feel a little as the collection goes on. And that reminded me that I try to do the same thing when I’m arranging story order in Tales From the Magician’s Skull. So maybe in doing that we’re messing with the editor’s vision. Sad to say I’ll probably keep reading it in the order I want, but I’ll do it with a little regret…

On the other hand, if it’s a single author collection assembled after the fact by other hands, I try now to read one or two, then set it aside so that I don’t get too much of the same prose flavor and then fail to note the brilliance. I have to do this with creators of really rich prose, like that of Clark Ashton Smith or Tanith Lee. I’ve also had to do it with authors whose tales can feel a bit repetitive, like Moore’s Jirel of Joiry or the Solomon Kane tales of Robert E. Howard.

If it’s a singe author collection where the tales are in sequence, though, and the tone varies, and there’s an ongoing arc, like, say, my fave Lankhmar book, Swords Against Death or the Khlit the Cossack stories of Harold Lamb, I think there’s more to be enjoyed if they ARE read in order. When they feel like a mini-series, reading them out of order is a disjointed experience.

@18 Cyrion! That remains one of my favorite of all of Lee’s works. I probably ought to get around to *Birthgrave*, which I’ve heard hits some similar notes, although it’s not a fix-up.

Great article, guys. Keep this sort of content coming. There’s so much amazing fantasy that gets rolled under the juggernaut of Sanderson/Martin/Tolkien. As far as the question of markets for short epic fantasy, well… I think most of the demand for that has gone to indies. If trad publishers don’t want novellas or short fiction, and readers are looking for it, the indies will meet that demand in droves.

Good shoutout to Charles Saunders – the first two Imaro sword and soul novels were fix-ups.

Great discussion! Leigh Brackett really deserves far more mindshare than she gets from the general public. The same woman who wrote The Empire Strikes Back’s first pass script also wrote El Dorado, the most iconic Western of John Wayne’s mid-career, IMHO, in addition to the excellent short and novel length prose Howard listed. That’s a talent that should be remembered.

Closing in on finishing Lord of a Shattered Land, and I think it’s legitimately possible that we could see a resurgence in this sort of format of linked but self-sufficient stories forming a prose, “season.”

Also, if you’re a fan of Leigh Brackett, you really need to check out Monalisa Foster’s, Threading the Needle coming out on December 5th. It’s very reminiscent.

@21 Thanks, Tim. I concur that the indies definitely have some great stuff that is too easily overlooked. And clearly Tor.com is also recognizing the utility of novellas. I think readers are hungry for short fiction, especially of a serial nature, but that publishing as a whole hasn’t quite woken to the fact.

@22. I loved Imaro, and Charles Saunders was a treasure. I was lucky to have known him, albeit slightly, and am thrilled he had read and loved my first published novel, The Desert of Souls. Alas, our email chain is vanished, along with one of my older laptops.

I hope his work is collected properly in some kind of master edition. I understand that there are still some uncollected short stories.

@23 I was already planning on checking out Monalisa’s debut novel, but if you say there’s some Brackett influene I’ll definitely move it higher on that tottering TBR pile!

Hope you’re enjoying Shattered Land!

Todd (@12): The nice thing about starting with Lin Carter’s Amalric stories is that they are self-collected. Carter included them in Flashing Swords #1 and #3, so you get a lot of other good fantasy/s&s stories to read, too.

Great stuff! Glad to see you guys resuming these conversations.

Short epics sound counter-intuitive, but before the big, fat, booklength epics that everybody knows about (e.g. the Iliad and the Odyssey), there were shorter, orally composed poems that were something like short stories. You can actually see that in epic traditions like Old Norse, where there are a lot of short songs of epic adventure (like “The Waking of Angantyr”, “The Lay of Fafnir” etc) but no big epic about, say, Sigurd the Dragonslayer because the native poetic culture was disrupted by influences from southern Europe.

Since I commonly walk among the dead, I should probably also mention the short epic fantasies from early in the 20th C. As Howard mentions, Lord Dunsany wrote some of these (e.g. “The Sword of Welleran” and “The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save for Sacnoth”). And James Branch Cabell wrote a lot of short fiction for magazines which he later assembled into booklength volumes–not quite novels, but collections of related stories set against a common background (like Vance’s Dying Earth). Some of these were fantastical; more were historical romances, but there were things like “The Thin Queen of Elfhame”. He wrote a book of short fantasies about the companions of Count Manuel (The Silver Stallion, 1926) and some of these are epic, even cosmic in scope. My favorite of his shorter works is “The Music from Behind the Moon”, though it begins with a poet and ends with a madman…. maybe not a big distance, as the crow flies, between those two points.

Whatever you call it (fix-up, episodic novel, etc), I love a booklength story that’s built out of individual stories. It’s a weird form, but I imprinted on it when reading Leiber’s F&G books, Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy, etc. etc. in the 70s. These things went out of style as the markets for short fiction dried up in the last quarter of the 20th C. But now that short story markets are rebounding, I hope to see more of these episodic novels.

And everybody should read Lord of a Shattered Land–a great modern example of the form.

Just so we’re clear: You’ll get my canal-crisscrossed, dying city-covered Mars and my jungle-clad Venus when you pry them from my cold, dead hands.

Great discussion! Another reason why I reluctantly agree that F&GM don’t quite belong in it — the other examples mentioned (Elric, Kane, Roland) all end up operating at epic scale, commanding great armies or battling potentially world- or reality-ending villains. I don’t recall F&GM ever getting up to quite those shenanigans although they certainly did have more than their share of encounters with gods and other beings of supreme power.

P.S. There was a great book of short epic sf/f stories early in the 21st C, too: Twenty Epics (All-Star Stories, 2006). Christopher Rowe’s story was only a couple pages long.

I have to confess the one Amalric the Man-God story I read left me very cold.

But Lord Dunsany — he was fantastic. The stories James mentions — “The Sword of Welleran” and “The Fortress Unvanquishable, save for Sacnoth” (what a great title!) — are the closest to epic fantasy, but he wrote dozens of supremely entertaining short fantasies. (Also he was Anthony Powell’s great-uncle by marriage, which I’ve always found cool, though likely nobody else cares.)

Honestly, as a reader, I prefer the episodic format. I grew up with Saturday morning cartoons and Batman the Animated Series, and always felt satisfied with the fact that each episode was a self contained adventure. I enjoyed literature that did that as well.

Now I write my own Sword and Sorcery stories, or throwbacks to pulp hero’s and the kinds of stories I loved so much as a kid. Granted, The Lord of the Rings is amazing, and can never be replaced. Still, not every story needs to emulate Tolkein, and not every adventure needs to be endless. I really appreciate that we are seeing a bit of a renaissance to short fiction. I hope it lasts.

@28 James, I love the short work of Lord Dunsany but I haven’t explored Cabell beyond Jurgen and another 1.5 of his works that Lin Carter gave us in the old BAF paperbacks. It sounds like you’ve provided some great insight into some goodies of his worth a look!

@32 I didn’t grow up with Batman: The Animated Series, but I love them anyway. The best of them — and the majority of those first three seasons are very good — are truly excellent and often moving storytelling. Not to mention the excellent animation and work with dark and light, and the wonderful voice acting, and music… I have always suspected, although I’ve never heard, that the writers were influenced by the original Trek, because so many of the best of B:TAS episodes conclude with that same bittersweet feeling at the ends of the strongest (especially first season) Trek.

I’m a very recent discoverer of Leigh Brackett and so, so glad to see her in more discussions sonthat even more of us can enjoy her brilliance. Also love the episodic approach! More fantasy for the win.

As I think about it, Alter Reiss’ Sunset Mantle strikes me as a fine example of an epic fantasy condensed into a single, standalone novella.

@36) I quite agree — “Sunset Mantle” is a lovely story, and Alter is an excellent writer.

Charles DeLint has created an entire world of threading together stories where someone who was just serving coffee to the main character of one story may be the main character of the next. He gives such great and steady depictions you can’t help but pick out faces in his crowds. It is a lovely thing to see.

No one has mentioned Roger Zelazny’s Dilvish, the Damned, which collects the short stories about the title character in a Del Ray paperback that appeared in 1982. Zelazny also wrote a novel about Dilvish (The Changing Land). And what about Michael Shea’s stories about Nifft the Lean? I would call these stories Swords and Sorcery and not Epic Fantasy shorts.

Thank you for introducing me to Leigh Brackett! I found that she has an impressive collection on Project Gutenburg: Enchantress of Venus is at https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/64043

I will certainly check these out. I am always on the search for great short stories, Science Fiction especially. I recently stumbled across Road Stop by David Mason and produced it on my podcast A Cup of Fiction. It’s about a haunted self driving vehicle! Dun dun dunnnnn… I have a few other sci fi shorts coming soon :)

Okay, as a newcomer to this corner of fiction (epic vs. sword and sorcery maybe makes sense (though if the fate of the world has to be on the line for an epic categorization, doesn’t that exclude the Odyssey and the Illiad?), but is not one that I use personally), first, thank you for all the new things! I am excited to investigate. The title of this post interested me, not only because of the oxymoron, but mainly because I expected to find other folks discussed here. In recent fantasy, as has been discussed above, there is less demand for short stories, but they are useful places for testing the waters, so to speak. Or, alternatively, as places to visit for a quick trip back. Garth Nix has great examples of the latter (Old Kingdom visiting in To hold the bridge, Creature in the case). N. K. Jemisin has great examples of the former (the Narcomancer leading to the Dreamblood duology, Stone Hunger and the Broken Earth trilogy). Do these belong in this short epic corner?

@39 Love Zelazny’s work and Dilvish, too. And Michael Shea is long overdue for a concentrated reprint. A gifted writer.

@40 There’s so much great Brackett to read! Have fun exploring her work.

@36 – Joe, thanks for the reminder about Alter Reiss’ Sunset Mantle. I’ve never read it, but I’m very curious about it — and if Rich Horton likes it, it must be good!

Reiss hasn’t written another novella since that one in 2015. But he has produced a lot of short fiction over the last year years, including “Recalled to Service” at Tor.com. I think I’ll start with that.

https://www.tor.com/2016/02/24/recalled-to-service-alter-s-reiss/

@38 – Finyol, I’m a huge fan of Charles de Lint’s delightful Newford tales. I’ll tell you a story — when I was trying to start a magazine in 2001, I REALLY wanted to have a story from a major writer in the first issue. I approached Charles with some trepidation, since it had been over a year since I’d run into him a few times in Ottawa.

He was enormously gracious and kind to me, and he delivered a fantastic Newford story, “Wingless Angels,” which we featured in the first issue of Black Gate magazine.

You’re right that we should have featured Charles’ Newford tales in the list. They started off as short fiction, and soon exploded into some two dozen novels and collections. I don’t consider the Newford tales “epic fantasy” (and I don’t think Charles does either), but they much loved, and deserved a mention.

@39 — Tom, you are absolutely right. We should have mentioned Roger Zelazny’s Dilvish, the Damned.

It fits all the criteria. It’s a series of epic tales of short fantasy (published chiefly in Fantastic Magazine, as well as Flashing Swords! and Whispers) that eventually grew into a popular novel (The Changing Land, 1981).

Yes, the novel appeared before the short story collection (Dilvish, the Damned was published in 1982), and it was never really a popular series — just those two books — but it’s still an embarrassing oversight. I blame Howard.

@46 Todd, that’s always the safest bet.

@41 — terrific question, BH!

I’m a fan of Garth Nix’s Old Kingdom stories, like “An Extract of the Journal of Idrach the Lesser Necromancer” and “To Hold the Bridge.” But to be fair I don’t think they fit in the same category as the epic short fiction cycles we’re talking about. For one thing, the novels in this series (Sabriel, Lirael, etc) came first by more than a decade, and the handful of short stories came later. It’s not really the same thing we were talking about, in which a series that began as linked short stories gradually grew in ambition and scope until it became a popular epic fantasy series.

N. K. Jemisin is the same thing, I think. “The Narcomancer” was published in Helix magazine back in 2007, and it eventually spawned the Dreamblood duology. It’s a fine example of using a short story to “test the waters,” as you say, but there was no series of linked short stories that grew into a fantasy epic. Different beast, to my mind.

@46 — Ha! I never realized that The Changing Land was published before the Dilvish the Damned collection.

Speaking of Zelazny, I’d suggest Jack of Shadows as short, epic fantasy; at least, as an edge case. Maaaaaaybe Lord of Light and Creatures of Light & Darkness, although I think those are more Clarke’s Law/van Vogt SF if you scratch under the surface.

@49 – Joe, I loved Jack of Shadows when I first read it decades ago, and you’re absolutely right. It’s a wide tale of science and fantasy in a gorgeously inventive setting that only Zelazny could have created.

I re-read it just a few years ago, and was appalled to discover that I had completely missed one of the most important aspects of the book in my youth. Jack of Shadows is pretty clearly the villain. Yes, he has a last-minute conversion in the last two paragraphs, but we’ll never know if that mattered (since he’s falling to his death).

Jack, like Lucifer, is intensely charismatic and iron-willed, but he’s also criminally self-centered and vain, and just about everyone around him suffers as a result.

Matthew Hughes has written many wonderful shorter works (short stories, novelettes and novellas) that he has then pulled together into collections. Many of his stories have a strong Vancean influence. I believe his latest collection is Cascor, which is a collection of stories about a character that is a private eye, some of which were previously published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. If you are a fan of Jack Vance’s Dying Earth stories or Michael Shea, you should give him a try!

Wasn’t Seth Dickinson’s Masquerade series, starting with The Traitor Baru Cormorant, originally created as a short story in Beneath Ceaseless Skies?